Housing, a pivotal domain within social policy, has been notably influenced by neoliberal tenets emphasizing deregulation and non-intervention in the market. This applies also to Iran over the past three decades. Minimal investment risk in the housing sector has transformed rental practices into an attractive way to generate income for certain interest groups, but affecting people's capacity to access housing.

Access to housing continues to represent a major challenge for Iranians and demands critical policy interventions. Iran underwent key land reforms in the 1960s and again in the 1980s. Despite these reforms, the value of land and rental practices have remained remarkably high. The allure of housing investment has reached such heights that even banks have entered the market extensively. The extent of banks' investment prompted the Ministry of Economy to issue regulations in 2022 restricting their entry into the housing market. And yet, there are still about 30,000 vacant housing units linked to banks. This situation has led Iranian housing policy researcher Kamal Athari to characterize the Iranian system as ‘neo-feudalism’ due to the abundance and profitability of rental properties, and to claim that the real estate bourgeoisie in the country has hindered the implementation of social policies in the housing sector.

The housing market before and after 1989

Ongoing research on access to housing and the housing market in Iran currently focuses on the post-1979 revolution. During the first decade since the 1979 revolution, the government held a monopoly over housing, which led to a number of relevant developments: private sector construction was generally halted, construction of housing units for individual or family purposes was promoted, and land access for low-income groups was provided by the state. As could be expected, the construction of new housing units during this period temporarily hindered the growth of the real estate market.

This phase is significantly different from the subsequent ones. After 1989, the Iranian government implemented the Structural Adjustment Plan (SAP) under the influence of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. This resulted in privatization, government downsizing, and deregulation, which significantly impacted the housing market by creating an intensely deregulated market in the following years. Since then, real estate has seen a significant increase in speculation due to the lack of restrictions on property transactions and pricing, as well as minimal taxation. Despite the introduction of some regulations, such as rent ceiling increases, government enforcement has been lax in practice.

It is worth noting that the only change in housing policy since the 1990s has taken place in the form of an intervention in the housing supply sector. Between 2006 and 2012, the government initiated the 'Mehr Housing Project' in 2007 to develop housing for low-income groups. This was possible thanks to the revenue produced by the surge in oil prices during the early 2000s. While the intervention focused on increasing the supply of housing, the government acted as a housing producer without implementing regulations or controls over housing prices, taxation, and similar measures.

With the decline in oil revenues after 2012, state intervention in ensuring housing supply also halted. The financial resources for the continuation of Mehr Housing construction were either absent or significantly delayed, even in cases of already issued residential building permits, in open contravention of the country's laws.

Growing costs, reduced offer

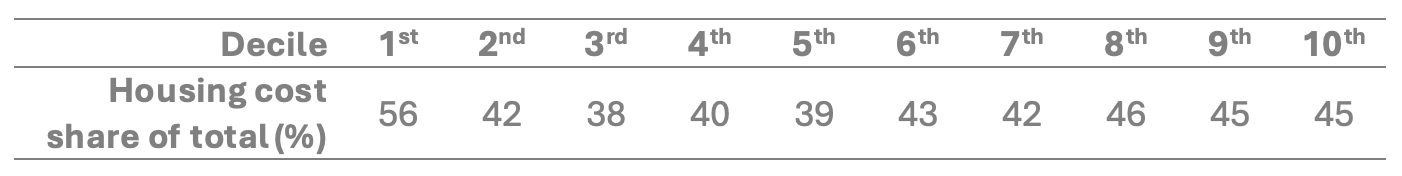

The government's avoidance to intervene in the housing market, both in terms of supply and regulation, has unequivocally led to inflation and substantial growth in housing prices. In fact, in certain years, nearly half of household expenses in major cities were allocated to housing. According to data provided by the Iran Planning and Research Center (IPRC) in 2023, approximately 56% of household expenses in the first decile in Tehran were routed to housing. This financial burden highlights the challenges faced by households in meeting costs and emphasizes the urgent need to reevaluate current policies and address the escalating impact on citizens' economic capacities.

Table 1 - The ratio of housing costs to the total expanses of an urban household in Tehran

Source: Islamic Parliament Research Center (IPRC). 2023. Performance of Legal Provisions

of the Sixth Five-Year Development Plan in the Housing Provision for Low-Income Strata.

Serial Number: 23018930. Tehran: IPRC.

The data confirms existing research that shows the limitations in Iran’s housing policies since the 1990s, aligning with the country's neoliberal agenda. Iran has very lax regulations regarding initial rent levels, regular rent increases, and deposits, this is in contrast to almost all OECD countries, as reported by the OECD in 2021. As illustrated below, the annual growth rate of rental units in Tehran has increased by an average of 20% per year between 1990 and 2021, indicating substantial growth.

Figure 1 - The ratio of housing costs to the total expanses of an urban household in Tehran.png)

Source: Islamic Parliament Research Center (IPRC). 2023. Expert Opinion on the Report

of the Construction Commission Regarding the Regulation Plan for the Land, Housing, and Rent Market.

Serial Number: 18939. Tehran: IPRC.

Housing policy, and the lack thereof, has significantly changed homeownership rates since the 1990s. The percentage of home ownership among households has been consistently decreasing, while households living in rental increases. In fact, the percentage of households that rent has more than doubled, escalating from 12.5% in 1986 to 30.7% in 2016.

Renting and policy responses

Although Atehari's neofeudalism concept has been perceived as radical and not widely embraced, evidence such as the significant profitability of renting alongside government non-intervention in the housing market prompts any observer to reconsider the peculiar amalgamation of neofeudalism and neoliberalism.

The convergence of historical inclinations towards housing investment and the deregulation of the housing market has created challenging conditions for Iranians to attain homeownership. Based on our analysis, we estimate that an average household in 2020 would require approximately 49 years to be able to buy a home due to the high rent expenses they must deduct from their income. The Iran Planning and Research Center (IPRC) reported that the age of homeownership increased to around 37 years in 2016, while housing prices surged approximately tenfold between 2018 and 2023. These alarming trends underscore the pressing need for a comprehensive reevaluation of housing policies to address the considerable difficulties Iranians face to access affordable homes.

In these circumstances, offering houses for rent is a highly secure and low-risk investment. As Athari notes, the real estate bourgeoisie wields significant influence in policymaking and decision-making, enabling them to shape policies in their favor or against policies that go against their interests. For example, legislation mandating the provision of insurance for construction workers have been met with resistance. Workers currently pay for their own insurance, while the employer's share is treated as a form of taxation and imposed on housing developers. Despite the challenges faced since its enactment in 2008, this law has proven to be effective. The Iranian Social Security Organization has been successful in collecting employers’ contributions, alleviating burdens on the organization.