The concept of 'social policy by other means' has gained attention in recent years. It refers to policy interventions that serve as functional equivalents to traditional welfare state policies, but are not usually considered as social policy instruments. These interventions can play an essential role in the social protection of marginalised groups. Unconventional social policy is most likely to be practised by states with low intervention capacity and high informality in state-society relations. It is thus more likely to be found in the Global South, although it is also found in the Global North.

The debate on what exactly constitutes 'social policy by other means' is still in its infancy. Conventional research generally defines social policy by intention and motivation: the implementation of social rights, material redistribution, or political constraints on capitalist markets. However, alternative social policy approaches are often not based on social rights, only sometimes contain elements of redistribution towards the poor, and usually do not constrain market processes. Even the intention of policymakers to create welfare and social protection is often questionable.

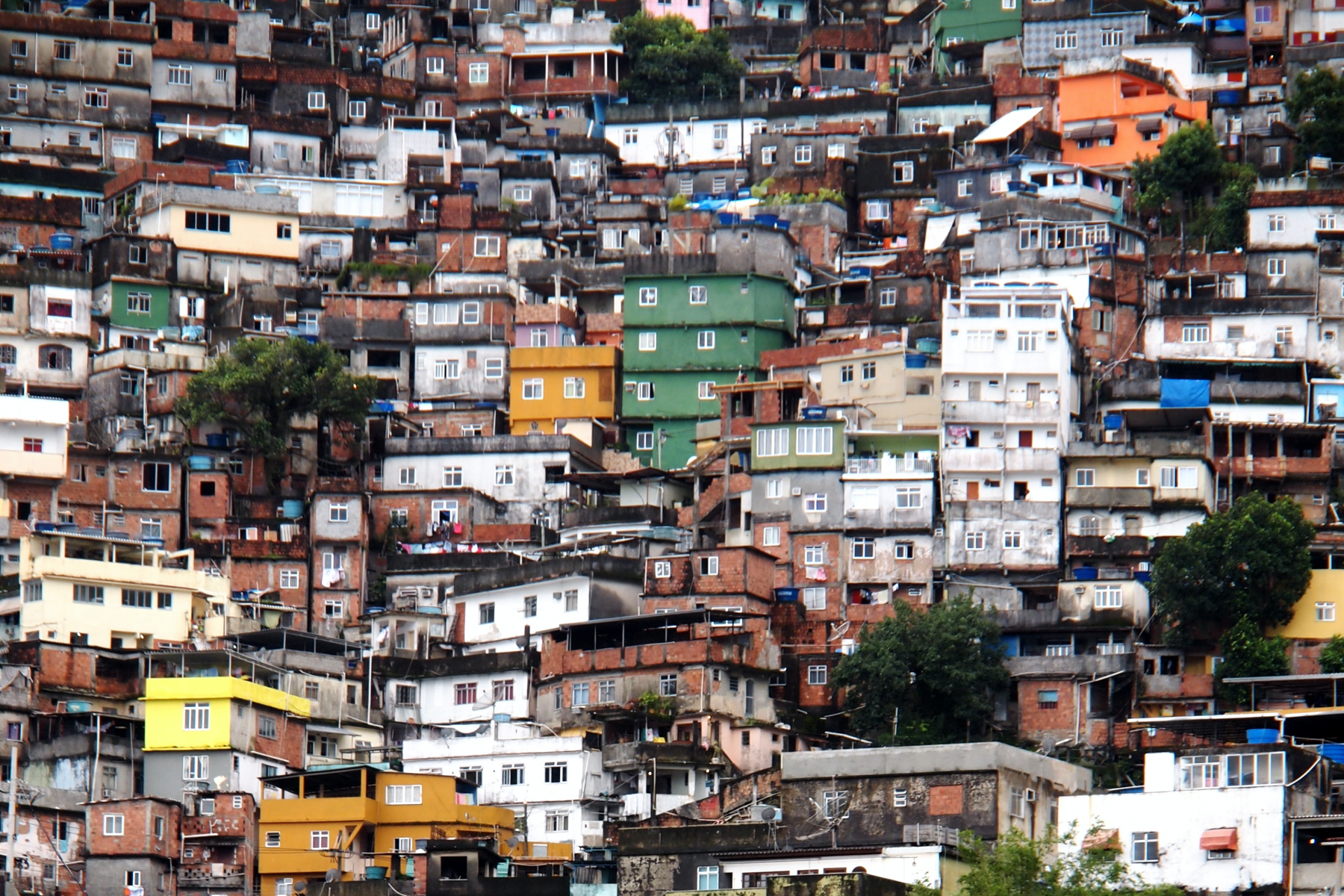

Still, ‘social policy by other means’ can help us understand the welfare effects of public policies. Here, I focus on how that applies to informal settlements and informal housing.

Housing policies as social policy

The majority of the world’s population now lives in urban areas. Rapid urban growth worldwide, particularly since World War II, has brought housing to the forefront of cities’ development. Housing has become an issue with a truly global dimension, also from a welfare perspective. Yet, while just under one-fourth of the global urban population, or 1.059 billion people, resides in “urban slums” (as defined by UN-HABITAT), welfare state research has not truly focused on housing policy as a social policy.

Ulf Torgersen notes that housing is "the shaky pillar under the welfare state". He argues that, unlike other areas of welfare, housing is seen primarily as a market commodity, rather than as an essential element of public welfare.

But asset-based welfare, meaning state support for the purchase of privately-owned housing, is comparatively well-established. When governments help residents to buy property, homeowners can, at least in theory, use their wealth as a safety net. The US and the UK, in particular, have supported private homeownership through a variety of financial instruments. In the Global South, Singapore has developed an elaborate, highly regulated and largely successful system that links citizens' housing loans to other aspects of their social savings.

Approaches to Informal Settlements

Policy approaches to informal settlements are instead often presented as individual cases of states or cities. A rare cross-national comparative study by Xuefei Ren, comparing China, India and Brazil, focuses on 'the different policy choices that local governments use to target informal settlements'. The study argues that four policy factors, namely: the relationship between the central state and local government, electoral politics, municipal finance, and civil society capacity, are crucial to understanding policy and welfare outcomes. It shows that many policy approaches are temporary or even situational, limited to selected locations, and subject to changing tides of political contestation and economic development.

Moreover, public authorities use a limited set of instruments to deal with informal settlements. From this sample of middle-income countries, it appears that the spectrum ranges from the threat of violent eviction to quiet acceptance of squatters' presence, from complete neglect to the provision of social services and basic infrastructure, and from eviction to formalisation and legalisation of settlements. Some of these approaches can enhance the social protection of informal settlement dwellers and thus amount to 'social policy by other means'.

In southern Europe, the widespread practice of 'self-promotion' on weakly controlled public land testifies to the importance of home ownership as a form of social protection tacitly accepted by the authorities. In Greece, after World War I, the authorities openly tolerated the informal building activities of refugees from Asia Minor. In Italy, 10-15% of dwellings, mainly in the southern part of the country, were built without formal planning permission. Retrospective legalisation has been a recurrent political response.

In Turkey, informal housing on public land, called 'gecekondu', spread after World War II. By 1980, 72% per cent of Ankara's population lived in gecekondu. While newly built informal housing was often demolished, a series of amnesty laws secured the legal rights of residents in selected settlements, where the state also invested in basic infrastructure. From 1984, the distribution of land titles to residents became widespread. Public companies provided electricity, water and telephone services. In 2004, however, the national government criminalised the construction of gecekondu; the new legislation prevented new squatting by forbidding the provision of public services, and in particular, of water. In the following years, gecekondu residents received housing units in exchange for their land, provided they paid a price difference.

South African public approaches to informal urban settlements have also undergone extreme changes. During the apartheid period from 1948 to 1994, a sprawling system of townships emerged on the fringes of 'white' cities. Public investment focused on infrastructure for cheap labour, such as transport, while other forms of infrastructure and social services were minimised. Following democratisation in 1994, the new government invested heavily in standardised 'starter' houses. In 2004, the government adopted a new focus on 'upgrading', resulting in the replacement of existing buildings with formal housing. Residents saw land and house deeds as one of the most positive developments for their social situation, but electrification also improved their social protection.

Social protection and social differentiation

Given the importance of housing for social protection, and the complex relationship between housing and other social policies, it should be redefined as a social policy instrument. Welfare should include informal housing as an area worthy of study, not least because it offers an opportunity to overcome the self-imposed limits of social security welfarism in Europe.

But what are the implications for social protection? The tacit acquiescence of public authorities to land squatting, perhaps the most widespread approach to urban housing issues worldwide, can be understood as a temporary but inadequate form of social protection: ‘at least,’ informal settlement residents are not made homeless and their dwellings are not destroyed. Regularisation and formalisation of housing and land tenure can also promote social protection. The provision of basic infrastructure, safe water, electricity, health and education services often has the same effect.

However, all these approaches - including acquiescence - can lead to processes of commodification of formerly public land, followed by cycles of social differentiation and growing inequality among residents. In several cities, researchers have observed how, even before formalisation, residents and outside investors, working informally with local authorities, have created profitable markets. Regularisation and titling, while a form of 'asset-based social policy', can accelerate processes of commodification. Such developments intensify as cities grow and former suburbs become central locations. Formalisation can accelerate gentrification, resulting in the exclusion of residents from their former settlements.

Header photo by David Araeva - Unsplash