Comparing Argentina and Chile, this essay shows how immigrants’ access depends less on ideology than on whether policies are framed as universal or targeted for citizens, revealing deep inequalities in inclusion across social programs.

In the early 2000s, Latin America expanded its welfare states at a scale rarely seen before. Governments poured resources into social assistance, pensions, and health care. Millions of citizens accessed benefits for the first time, helping reduce poverty and inequality. At the same time, and unrelated to that social policy expansion, the region experienced a historic immigration boom. By 2022, the number of immigrants had doubled in just over a decade, reaching 16 million people.

These two forces—expanded welfare and rising immigration—raised urgent questions. Would immigrants be included in new social programs? Would they receive equal treatment as citizens? And why would access differ across types of policies?

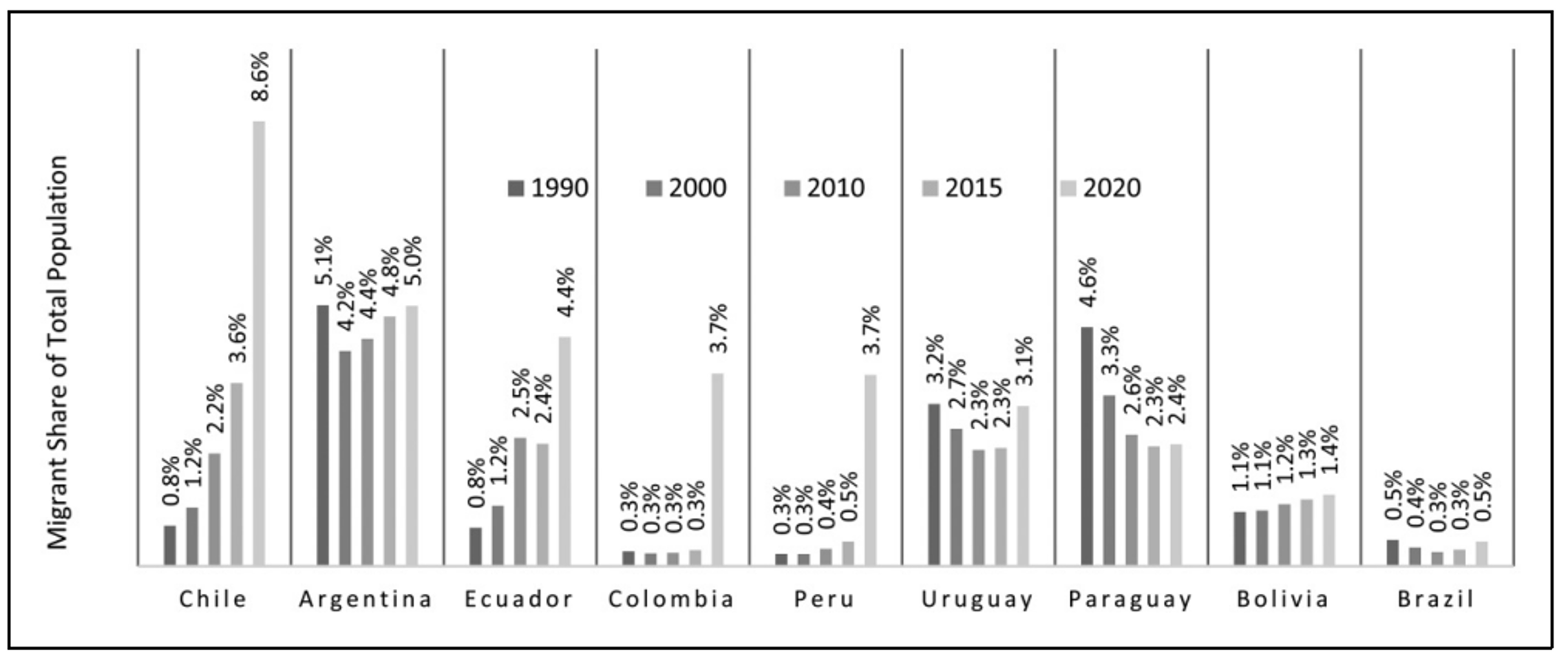

I shed light on these questions in a recent open-access article, examining Argentina and Chile, the South American countries with the largest shares of foreign-born residents (see Figure 1 below). Using legal analysis, administrative records, and 80 in-depth interviews with policymakers, Niedzwiecki shows that immigrant access depends less on political ideology than on how policymakers perceive different types of programs.

Rights Versus Costs

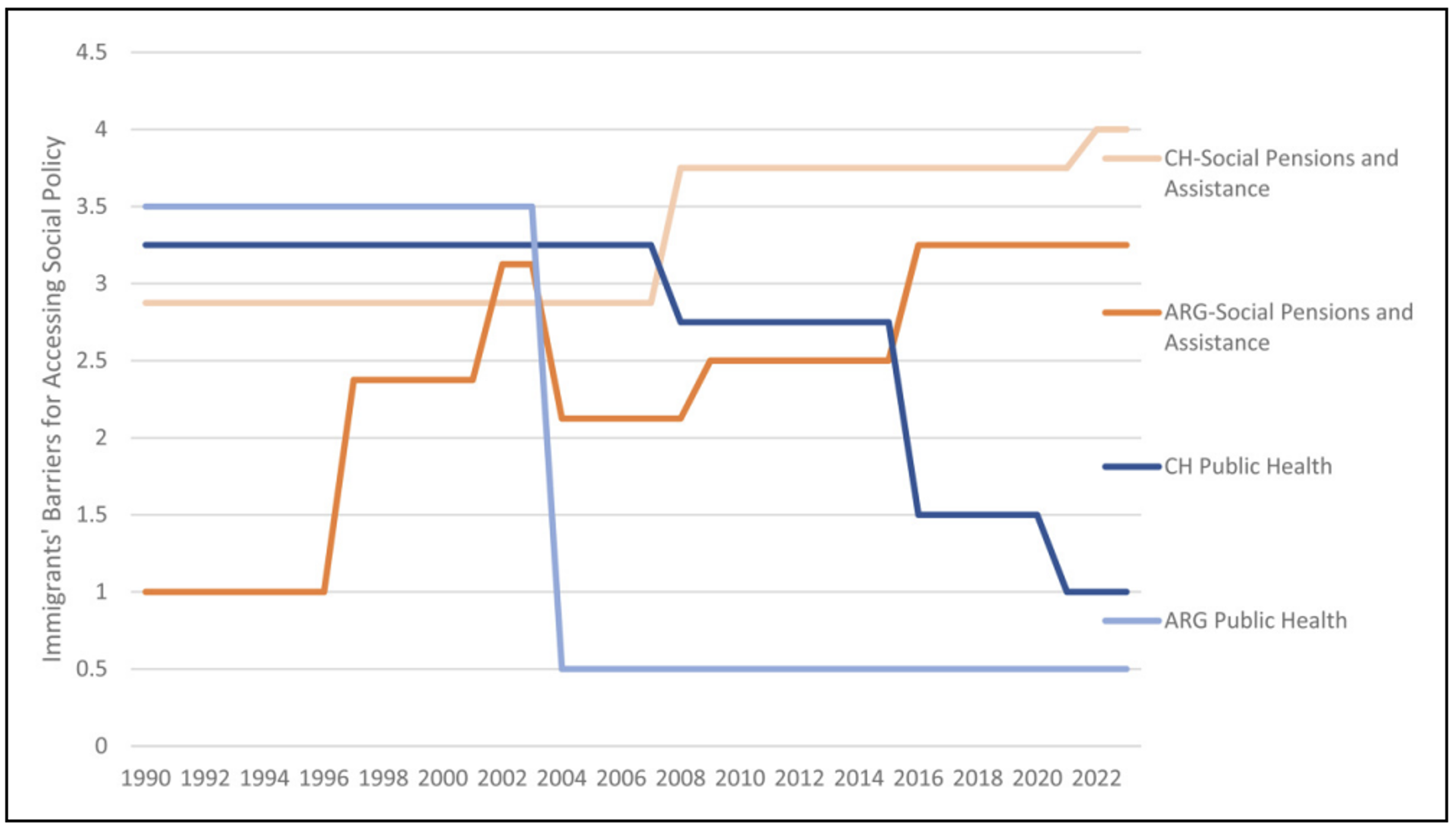

The study’s central finding is that immigrants face different barriers depending on whether a policy is universal or targeted.

Universal policies, such as public health care, are generally understood as social rights. Political elites believe they must cover everyone within a country’s borders, including immigrants. Barriers to immigrant access have therefore declined in these sectors.

Targeted policies, such as conditional cash transfers or social pensions, are viewed as costs to be contained. Because they are aimed at specific groups, often the poor or elderly, officials worry that immigrant access will stretch limited budgets. Barriers have increased in these programs, even as they expanded for citizens.

This framework helps explain the contradictions within Argentina and Chile where immigrants gained access in some areas but faced exclusion in others. Figure 2 shows that barriers for immigrants increase for targeted social pensions and social assistance over time while they decrease for public health care in both Argentina and Chile.

Argentina: A Rights-Based Tradition With Limits

Argentina has long attracted immigrants, particularly from neighboring countries. Its landmark 2003 Migration Law embraced a human rights approach, affirming immigrants’ access to health and education. Civil society organizations played a key role in pushing this reform.

Regarding health care, Argentina’s public health system is universal by design, and politicians across the spectrum frame it as a right. Even undocumented immigrants are entitled to free care in most cases. Officials repeatedly stressed during interviews that health care cannot be denied on the basis of immigration status.

However, looking at targeted programs, access to social assistance and pensions has become more restrictive. Non-contributory pensions can require up to 40 years of residency in Argentina. Administrative agencies also interpret eligibility strictly. As a result, immigrants make up only a tiny fraction of recipients, far below their share of the population.

The contradiction is clear: Argentina embraces immigrants’ right to health care but restricts their access to targeted transfers, citing fiscal scarcity. This is puzzling because delivering healthcare is much more expensive than providing a cash transfer.

Chile: New Destination, Higher Hurdles

Unlike Argentina, Chile only became a major immigration destination in the past decade. The foreign-born share of the population jumped from under 1% in the 1990s to nearly 9% in 2020 (Figure 1), largely due to Venezuelan and Haitian migration. Until 2021, Chile operated under a restrictive dictatorship-era migration law, which shaped immigrants’ access to welfare.

With regard to health care, Chile’s public health system mixes universal and targeted features. Initially, immigrants faced high barriers—access often required a Chilean ID, excluding many newcomers. Over time, reforms lowered these hurdles, first for pregnant women and children, and later for all immigrants regardless of status. Still, delays and administrative requirements mean many immigrants remain outside the system during their first years in the country.

Non-contributory pensions and social assistance, in turn, have imposed steep hurdles. Residency requirements rose from three years in 1990 to 20 years by 2008, making it nearly impossible for recent immigrants to qualify. Access to poverty-targeted transfers also depends on a Chilean ID, effectively shutting out undocumented residents.

Chilean policymakers consistently described immigrants accessing both health and social assistance programs as a “fiscal burden,” reinforcing the logic that targeted benefits must be rationed. The Chilean case also shows that this is not a story of healthcare versus social assistance, but of universal versus targeted designs.

More Than Ideology

One might expect that left-leaning governments would be more inclusive of immigrants, while right-leaning ones would be more restrictive. The study shows otherwise. In both Argentina and Chile, politicians across the ideological spectrum defended immigrant access to universal services while restricting targeted benefits.

The decisive factor is not ideology but policymakers’ perceptions of who should access and to what policy. If policies are social rights of citizens as in health in Argentina, immigrants will be included. If they are not a social right for citizens, then immigrants are seen as an economic burden.

This insight challenges assumptions drawn from Europe and North America, where ‘welfare chauvinism’ often pits natives against immigrants across all types of programs. In Latin America, the divide runs along policy design—universal versus targeted—rather than political ideology.

Conclusion

The expansion of social policy in Latin America lifted millions out of poverty. Yet, for immigrants, the picture is uneven. In Argentina and Chile, universal policies have become more inclusive, while targeted programs like social pensions have grown more restrictive. This divergence reflects not just laws or budgets, but the ways policymakers think about social policy. When programs are framed as rights, immigrants are included; when framed as costs, they are excluded.

This finding has implications beyond the two countries and the region. First, it spotlights insights from the Global South in debates about welfare and migration. Most scholarship on these issues has focused on Europe and the U.S., but middle-income democracies face different constraints, including widespread informality and limited fiscal capacity. Second, this study highlights immigration status as a key axis of inequality. Latin American social policy studies often emphasize class, gender, and region. Adding immigration status reveals how welfare states stratify populations further. Third, it evidences the importance of policy type to understand inequalities. Access is not uniform across sectors. Understanding why barriers vary helps explain otherwise puzzling inconsistencies.

As for Latin America, as immigration continues, these tensions will sharpen. The challenge for policymakers will be to reconcile fiscal limits with the principle of equal rights for all residents. The choices they make will shape whether immigrants are incorporated into the social fabric—or left at the margins of the welfare state.

This article presents findings from 'Immigrants’ Barriers to Accessing Social Policy in Argentina and Chile',

published on International Migration Review.

Teaser photo by Gustavo Sánchez - Unsplash

Header photo courtesy of Sara Niedzwiecki