Workers' have taken to the streets in the past two years in Kazakhstan and Russia. A novel dataset offers us insight on why workers are mobilizing, and why they are choosing institutional or extra-institutional channels in each case.

Kazakhstan is one of the largest post-Soviet countries that has retained many traditional Soviet features in the economy, such as the focus on the production of natural resources, as well as authoritarian governance in the political and legal sphere. In January 2022, an acute political crisis arose: riots took place in an alleged coup d'état, which were repressed only with support from Russian troops, which were sent to Kazakhstan and later withdrawn. Russia faced a crisis of its own after it launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which led to substantial upheaval in politics and the economy.

Formally, the crisis in Kazakhstan was resolved swiftly – partly due to brutal police crackdowns that caused several hundreds of deaths in the wake of protest repression. But economic and social tensions have persisted, while the number of workers’ protests has almost tripled since 2021. This might be because workers’ protests often become a trigger for protests in other spheres. This peculiarity is relevant for Kazakhstan, as, quite often, workers’ protests are supported by citizens with their own grievances. (see Isaacs 2022) In other words, labour protests "absorb" communal, environmental, and social protests and, in turn, serve as a breeding ground for broader, political protests. For example, in April 2023, residents of the city of Zhanaozen went to a rally in support of the miners who left to protest in the capital of the country and were arrested there. As a result of the protests, the arrests were released, and negotiations began with them.

What is driving this wave of protests, and why are workers choosing some forms of protest over others? We have captured the recent wave of labour protests in the Monitoring of Labour Protests (MLP) database, which comprises data on conflicts during 2021 and 2022 for Kazakhstan, and compare the protest wave with similar trends observed for Russia.

Why are workers protesting?

The reasoning of mobilizing protesters is the most important parameter to understand what exactly is driving workers to step over the boundary of customary and traditional relations and switch to alternative forms of expressing their demands. In Kazakhstan, the main mobilizers are low wages and changes in the wage system, which have decreased slightly from 2021 to 2022. Other reasons remain consistently high, such as the lack of payment of due wages, and others remain consistently low, such as fear of dismissal and redundancy.

Particularly interesting are responses under ‘Other’ in our dataset: for instance, in 2021, employees of Kazakh enterprises cited ‘rudeness of bosses’ as one of the reasons for protesting, while in 2022, the most cited additional causes to mobilize were demands to nationalize the company and disagreement with transfers to outsourcing companies.

Causes for protest among Russian workers appear different and less dynamic than those of workers in Kazakhstan. There is substantial change only among those reporting the non-payment of wages, while trends for other reasons remain almost unchanged. Other problems, especially in comparison with payment delays, appear less important – in other words, the conditions and how long one must work may not matter, as long as one gets paid.

In both countries, protests are rarely led due to employers’ refusal to negotiate. However, behind similar figures lies a very different reality. In Kazakhstan, negotiations almost always occur: even if employers do not intend to, local authorities are prompted to lead negotiations, and eventually, some form of dialogue takes place, either in goodwill or under pressure from the administration. In Russia, this reason is barely reported because workers know the futility of negotiations. For example, in recent years, taxi drivers working with digital platforms have led the most important strikes to protest changes in payment systems. Companies running payment platforms regularly undercut fares and categorically refuse to discuss these issues with drivers. There is little space for workers to negotiate with those companies.

This dynamic shows that in Kazakhstan, workers are supported by the authorities, who force employers to negotiate but do not impose a specific solution. In Russia, workers do not wait for negotiations but prefer the authorities to intervene on their side and lobby for their interests.

Mobilizing, Negotiating, Striking

A protest is a conflict that is brought into the public space. However, he forms that each clash between employees and employers will take depends on which actions are accessible to employees and can produce some effect. More often than not, workers must rely on multiple channels, moving from ‘soft’ protests, such as presenting demands, to more hardliner responses, such as hunger strikes, blocking highways, or seizing facilities.

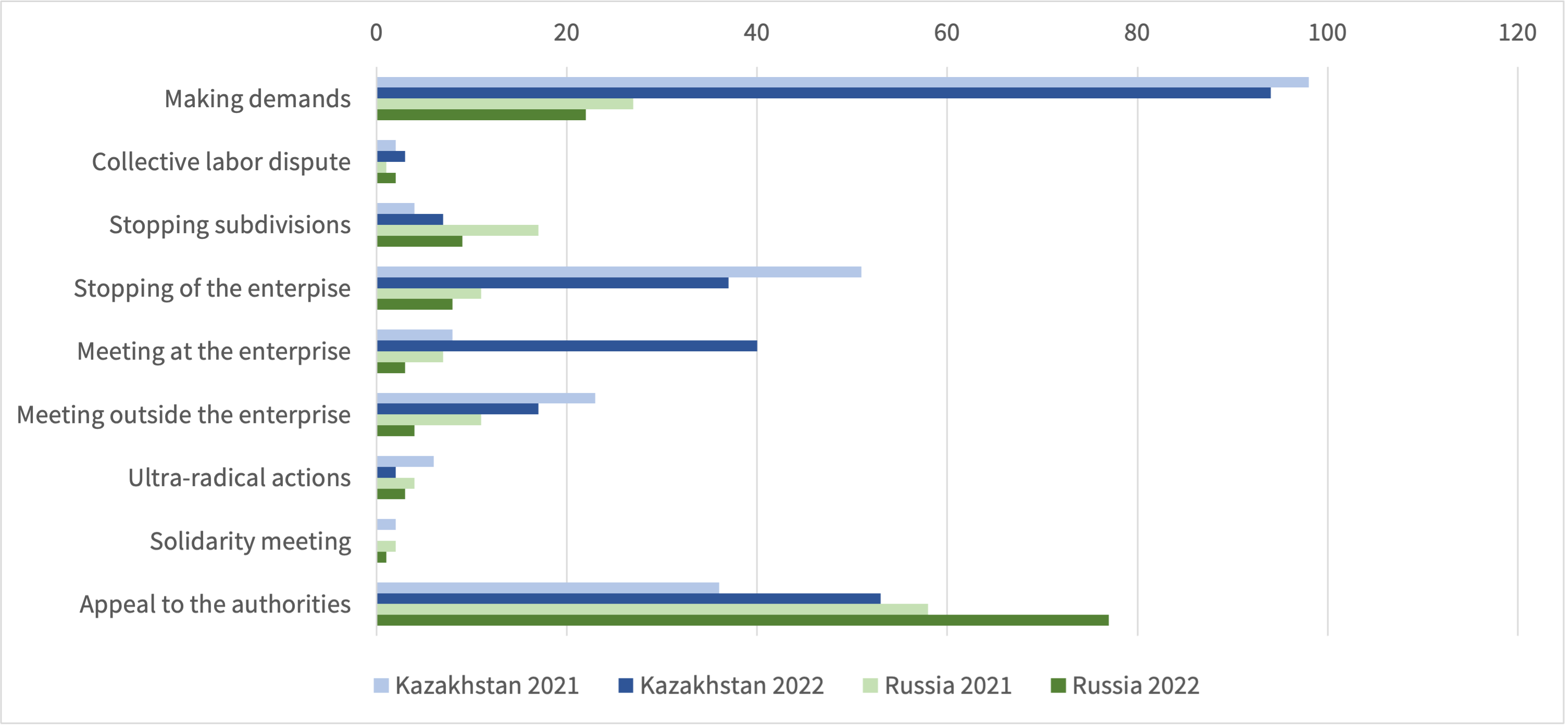

In Kazakhstan, workers usually first try to discuss with their employer, while in Russia, this minimal form of protest is used much less frequently (27% in 2021 and 22% in 2022). The next most common forms of protest in Kazakhstan comprise three variants: work stoppages, appeals to the authorities, and rallies at the enterprise. A work stoppage is a classic form of labour protest – the strike. In Russia, strikes are not employed very often (11% in 2021 and 8% in 2022), but subdivision stoppages are more frequent.

The reason behind this variation is that strikes are part of a labour dispute that involves a complex and lengthy procedure. Normally, the law on the resolution of labour conflicts aims at having the parties clarify the relationship and find solutions without going outside the company. However, if the law does not work, the conflict “spills out of the gate”, and the parties look to external actors to influence and help them. Therefore, both in Russia and in Kazakhstan, workers often organize rallies and pickets, both on the territory of enterprises and outside.

In both countries, legal labour protests take the form of collective labour disputes (CLTs), but they barely amount to 1% to 3% between 2021 and 2022. This means that collective labour law is not working well in either country and that conflicts most often move outside the institutional framework. Therefore, in both cases, a significant proportion of work stoppages occur spontaneously, without following the procedures prescribed by law. Because the legal framework fails, the concrete form of management of the conflict of interest is chosen spontaneously according to contextual factors and the current situation. The larger use of spontaneous strikes among Kazakh workers suggests greater sectoral cohesion.

Our monitoring considers all cases involving strikes and their proportion to the total number of protests. That proportion – the ‘tension coefficient’ – has remained high in Kazakhstan for the past two years, where every second protest was accompanied by a work stoppage. In Russia, instead, the tension has grown low – previously, almost every third protest was a work stoppage, while in 2022, only every fifth protest included a strike, the lowest point in fifteen years. Overall, there was a striking decrease in Russia, from 122 cases in 2021 to 72 cases in 2022, while the inverse trend was observed in Kazakhstan, with 32 stop actions in 2021 and 70 in 2022. The trend gains relevance when considering that the total population of Kazakhstan (19 million) is approximately eight times smaller than that of Russia.

Figure: Forms of labour protests in Kazakhstan and Russia, 2021-2022, in percentage

Figure: Forms of labour protests in Kazakhstan and Russia, 2021-2022, in percentage

(multiple selection was allowed, total amounts to over 100%)

Changing Forms of Labour Protest

In both Kazakhstan and Russia, recent protests are widespread as workers face unresolved grievances across the territories. Although there are significant differences in the reasons behind labour mobilization—for Kazakhstan, it is low wages, while for Russia, it is the non-payment of wages—workers in both countries are faced with little to no legal or institutional mechanisms to resolve labour conflicts. This, in turn, means that more actors are involved who might be left out of the legal framework, leading to the escalation from labour conflicts to socioeconomic and political protests.

In Kazakhstan, more emphasis is placed on dialogue with the employer, although 'hard' forms are also deployed, leading to the complete shutdown of enterprises. In Russia, there is little use of dialogue forms; the main emphasis in recent years has been on appealing to the authorities to ‘come to the rescue’ and take on the role of arbiter or ally. This is the position of the 'complainants', whereas in Kazakhstan, the workers appear to be the party demanding and seeking dialogue.

When dialogue and institutions fail to sufficiently address both labour and socioeconomic demands, workers are forced to look for alternative channels to protest. Trade unions could help, but in Russia, for example, the vast majority of protests are spontaneous (73% in 2021 and 74% in 2022). Only in 20% of cases do the primary or higher trade unions organize or join workers' actions. In Kazakhstan, the proportion of protests involving trade unions is even lower than in Russia (12% in 2021 and 4% in 2022). However, instead of spontaneous protests (down from 79% in 2021 to just 35% in 2022), Kazakh workers, with a share of 63% in 2022, are increasingly organizing protests through their own self-government bodies, many of which emerge as protests occur – essentially proto-unions that replace official trade unions when these are unable or unwilling to enter conflict resolution.